When I opened my first restaurant, I spent so much time there my mom sent me a twin bed for Christmas. The mattress company delivered it right to the back dock of the restaurant like a produce order. We tucked it in a corner of dry storage so I’d have a place to crash on the late and sometimes tipsy nights restaurant openings require.

For a long time that restaurant — at the end of a dusty alley in Santa Fe, New Mexico — felt more like home than my real home did. I knew its quirks, dimmer switches, fuzzy speakers, funky smells. I knew how to make it glow with music and flowers and candles so that when it filled up with people it seemed to lift off into another dimension.

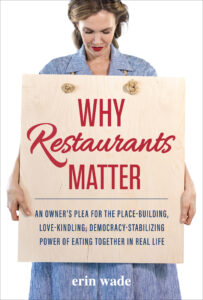

For the past ten years — all of my thirties, when my friends and baby sister were making babies and starting families — I made restaurants. We used the profits from each restaurant to build new restaurants, so by 2020, the year I turned forty, I had a family of six restaurants. Each one in a unique, historic neighborhood. Each one a part of its community.

Like most small business owners, I invested “sweat equity” to save money. In Austin my fiancé and I used hand picks to remove the asphalt under the 400 year-old Live Oak on our patio so we could plant a garden and build a deck in its shade. We would strike the hard black surface with the sharp side of the pick, which reverberated all the way up into my teeth, and then use the flatter side to pry up the crumbling pieces. It was summer in Austin, humid and over a hundred degrees. The air felt like the inside of a dog’s mouth. Jeff bought bags of ice and made me lie on them whenever I looked like I might pass out.

Later, he taught me how to use a nail gun so he and I and whatever friend we could beer-bribe to help us could install the tongue-and-groove ceiling in the dining room.

The value of a business is in its assets — cash, equipment, FF&E — and its future potential to make money. If an owner sells a restaurant, the price is set as a percentage of gross sales. Restaurants are “discounted” more than other kinds of businesses, like medical or dental practices, because our customers are more elastic and the business is riskier.

But restaurant owners knew how to handle those risks, and the sensitivity of our customers. We fuss over “guest perception” in order to create that ineffable “vibe” that makes one place madly busy and another place creepy. We worry about tiny, practically invisible details — straightening and lining up barstools, rolling silverware, polishing glassware, wiping the fingerprints off the front door.

And before the pandemic, we would never close for more than a day or two, because it could disrupt customer habits we had spent years trying to become part of. We also never complained about the troubling things hurting our industry, partly because we were too busy dealing with them, but also because it might make us seem whiny and weak.

Restaurants never minded being outsiders. Anthony Bourdain was our patron saint, after all. But when the pandemic hit, our outsider status meant no one in government really represented us.

During the pandemic, we were shut down repeatedly by elected officials who did not understand our business. They did not understand how important momentum is to everything we do, how much we require consistent cash flow to pay our bills or make payroll.

In the first week of the pandemic, when we had zero customers, no news about a bailout, and I had stopped paying taxes and vendors and drained my savings account in order to cover payroll for wages already owed, a city councilman in Albuquerque proposed a sixty-dollar minimum wage.

This would have made a typical monthly payroll at one of my restaurants a quarter of a million dollars, more than our highest monthly sales. But this elected official probably didn’t know what that means; many of our representatives didn’t seem to grasp the basic arithmetic small business must abide. And yet they were slinging policies at us like hash.

When Austin restaurants were shut down for a third time, and owners interviewed by the local news said they didn’t think they could make it through another closure, the mayor of Austin responded (I’m paraphrasing) “We’ll all order takeout!”

Takeout was the biggest misunderstanding of all. Lawmakers needed to believe that takeout would save us — it was the tiny sliver of a carrot that meant they hadn’t actually taken our livelihood. Even customers didn’t understand that takeout was an entirely different business model, and not the one we were set up for.

Takeout requires cheap production, low operating costs, and a skeleton staff — a food factory, not a restaurant. Restaurants are designed for public gathering, eating and drinking.

As the pandemic dragged on and on, the discourse shifted. Now the word “adapt” is as overused as “unprecedented” was two years ago. Since the pandemic accelerated existing economic trends, restaurants needed to “adapt,” or become “pandemic-proof.” An article in the The New York Times detailed how restaurants “unprepared for the digital age” relied on “tech helpers” to “redefine the experience” and “think outside the four walls.”

We so want to believe that our economy fairly rewards merit — that neoliberal idea that markets always know best. But the busiest, most successful restaurants were hurt the worst by the pandemic. The packed houses, where lines snaked out the door and down the sidewalk, where people proposed, had birthdays, family dinners, lazy lunches. Those places owe millions in back rent. Their balance sheets are shot. They were made to be slammed, not to sell cocktail kits online.

For restaurants, merit used to be rewarded by profit. A good way to tell if a restaurant was profitable, before the pandemic, was whether or not it existed — if we didn’t make money, we went out of business. But our biggest “disruptors” were delivery platforms who had no profit requirement — bloated with venture capital, allowed to merge into massive monopolies that are now publicly traded, they had and still have an endlessly open tab while they work out their faulty business model.

And yet, most people think that delivery apps are “adapted” in a way restaurants “unprepared for the digital age” are not. But like so many digital platforms, their business depends on dodging laws that have been put in place to protect workers and consumers.

Our business model is based on concentration — bringing people together in space (dining rooms) and time (meal periods) so we can more efficiently serve them. Every server understands this. They want to make their money in a couple hours, in the busy section.

Delivery apps, on the other hand, are based on dissipation — on the promise of delivering anything, anywhere, any time. This only works because they don’t pay for the actual costs of doing this — for workers, fuel, or food safety.

And they operate in an unregulated data economy. As Shoshana Zuboff has said, we haven’t failed to regulate Big Tech; we haven’t even tried. Brick and mortar businesses, on the other hand, are highly regulated and only getting more so. Economically, this absence of regulation in the digital world functions like a subsidy. So, while government should be protecting consumers against predatory data mining and digital invasions of privacy, it is effectively encouraging it.

The ad-based digital economy has created “asymmetries of knowledge and power” that make most small businesses less like autonomous entities and more like employees of Big Tech. We are dependent on data companies for access to customers with hyper-individualized data streams only a few companies can parse.

These trends were bad for democracy to begin with, tending towards solipsism and cynicism. But the response to the pandemic made them worse. With the small business economy shut down, and everyone scared, people had to buy everything online, which these days pretty much means from Amazon, or some other large, publicly traded company operating in a regulatory vacuum.

But for me the most chilling result of two years of disaster living, when every aspect of life moved online, was the way people began to defend this shift as an acceptable, even better, way to live. As if we can replace everything we used to do in real life with a screen or an algorithm, as if Facetime is as good as face-to-face time. Or, at least, “good enough.”

We now have special words for being together together — IRL, we say, or “embodied” togetherness. Plain old actually being together is no longer the default, but the niche.

I have spent my life creating public places where people can gather to eat and drink together. I know there is something special that happens when they do, something irreplaceable by anything digital, because I’ve seen it unfold in thousands of shifts — shifts I used to take for granted, like the sun rising.

Most restaurants are just trying to be there for our communities when this is all finally over — so the public will have a place to embody itself again.

This togetherness was essential to democracy.

Before the word “public” came to mean “ordinary people in general” as in “we, the people,” there had to be a place for ordinary people to gather. The places came before the concept. Before there was democracy, there were people meeting in taverns and cafes and coffeehouses, talking about it.

And I wonder, if these places disappear, will that meaning of “public” vanish, like a cloud swallowed by a relentlessly blue sky?