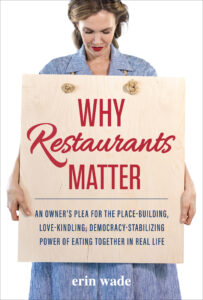

Pete Wells, the restaurant reviewer for The New York Times for the last twelve years, announced his retirement in the summer of 2024. He has been my favorite reviewer of the last two decades and I admired especially his final article, about how restaurants have changed since he began reviewing them. I wrote him a letter thanking him and sharing my thoughts, since my career in food spans that same period of rapid change (and, um, I’m writing a book about it that is, swear, almost, finally for real done, to be published in 2025). Anyway, the point is PETE RESPONDED. I’ve included his response beneath the letter I sent him, since I was beaming with pride like I had been thumbs-upped by Beyonce.

Dear Pete,

I am a restaurant owner in the Southwest, and want to thank you for your last article as restaurant reviewer for the Times. You have been my favorite critic of the last twenty years, and your perspective, and palate, will be missed. But I especially appreciate that you used your platform to voice the (not always popular) idea that screens, and convenience, don’t always improve experience. It says a lot about how uncritical we are of technology that the notions you expressed, which not so long ago would have seemed pretty practical, are today practically radical.

New York City has always been the benchmark food city for me, a place I go to eat, to experience what the best of the best are making. But on a trip to NYC taken just as it was was coming back to life after vaccine rollouts, I wrestled with many of the changes you mention, and tried to write about them in this article Why These Walls Matter, for the blog Life and Thyme. I called it the airportification of restaurants. I wrote about my growing concern that restaurants were becoming more like kiosks–but I like your term, “vending machine,” better.

It has been hard to watch restaurants clutter the human connection with screens. But it has also been hard to watch customers retreat behind them. When I opened my first restaurant in 2008, people still used phone books (at least in Santa Fe) and not everyone had smartphones. Today, it is not uncommon to see two customers at a table staring at their phones, not looking at one another, or the food, for an entire meal.

Good food, served in a particular place, used to have a kind of magnetism. You could hang your shingle, work really hard making and serving great food, and that was enough (and it was plenty of work!!). When I first opened, most of my customers still read the local paper, meaning we all sipped from the same broad data stream. If a new restaurant got a single review in a local paper or pub, it was enough to catalyze a much-needed opening honeymoon that accelerated slowly, lasted about six months, helped us pay off start-up bills and gave access to a large group of curious customers that we could convert to regulars.

Now customers get information from hyper-tailored data deltas. They are obscured behind preference bubbles. Local papers are in the weeds, or non-existent. This has turned us food people into de facto digital marketers, a job I never wanted. I can’t tell you how much time–that used to be spent on food–I now spend figuring out how to get through to customers. New restaurants especially have to blast myriad micro-sources–bloggers, influencers, listicles, listservs, websites, review sites, and news–in order to reach crucial break-even volume. And in order not to be forgotten by increasingly time-squeezed, harried diners, we must feed the social media beast three times a week, per portal, lest even more of our posts be withheld from followers’ feeds. Instead of a longer, more sustainable and convertible-to-real-life honeymoon, we get our butts kicked for a month or two after we open, and then people move on to the next new thing, leaving a debilitating cash crunch in their wake.

For a while, as you point out in your article, it seemed like restaurants would be safe from the “disruption” that was racking every other consumer-facing industry–because food is so emotional, so foundational to culture itself. It gave us restaurants a kind of super power. But the power screens have over us, now, is stronger. What I feel about this, I realized recently, is grief. Bone-deep grief for the loss of something that happened when place alone contained experience. When the only way you could have what we offered was within our four walls. This made us inwardly focused, lit from within by friends and strangers come together, to breathe one another’s air, to be nurtured and buoyed and softened by food and drink. I know this to be a magical, important thing. I hope it persists.

Erin Wade

Here is Pete’s very sweet response (and he is not exactly known for being warm and fuzzy; although I admit to wondering whether or not he meant “remarkable” like Seinfeld meant “breathtaking” about the ugly baby.)

Dear Erin, what a remarkable letter. (Or email, if you prefer, but I imagine you don’t.) I too feel some grief about what we’ve lost. I didn’t realize it until I wrote the article and am still coming to understand the depth of the mourning that I and other people feel. I don’t think I’ve ever written anything that touched a nerve in so many readers.

I wish I could share what you’ve said here–wish, in fact, that my paper still printed letters from readers. Of course it doesn’t, because blogs, Instagram, Facebook and other electronic media have supposedly made letters to the editor obsolete.

Pete