Erin Wade learning how to cook with her grandmother

In the 1980s, my grandma drove a Plymouth Champ. It was one of those tiny two doors with good gas mileage—like a Gremlin or a Pacer—that was churned out in the aftermath of the oil embargo. Hers was brownish yellow, the color of good Dijon. One spring afternoon, my mom and grandma were cleaning the house for garden club when my mom realized she was short coffee mugs. These were the early, heady days of Martha Stewart—paper cups freshly shunned—so Grandma took off for her apartment to get the good mugs.

A mile into her journey, Grandma and the Champ were broadsided by a carload of teenage drivers who ran a stop sign. The Champ was totaled. Undeterred, my whiplashed grandma unfolded herself, spoke to the police, and hitched a ride from the nice gentleman who witnessed the accident—first to her apartment for the coffee cups, then back across town to our house, just in time for the party.

The fact that I share genes with someone who managed to get the damn party mugs even after she was T-boned in a tin can, is perhaps why I have survived, thus far, in the restaurant industry.

But I’ll never be as tough as my grandma. She was from that generation that was born into war, came of age in the Great Depression—when people saved bits of string and patched their underwear—and entered adulthood just in time for another war. On top of this, my grandma’s husband—the love of her life—died of cancer not long after they had moved away from her closest friends and family.

Despite it all, I never heard her complain. But she wasn’t particularly fawning or lovey-dovey. What we think of as nurturing, nowadays, usually involves talking about our feelings, working them over like bread dough. Grandma didn’t go there: She rubbed your feet and made you a good meal—fried chicken, mashed potatoes with gravy, and chocolate cake, if you were really broken-hearted.

A lot of people bandy about the expression “food is love,” but they don’t exactly mean it. My grandma would never have said something namby-pamby like that, but cooking was how she loved. Mealtimes during the holidays, with my mom and aunt and grandma, crowded together in the kitchen, squawking about what they were making and would make, peppering one another with cooking questions they already knew the answers to, was when she was happiest.

Nowadays, we might say she had an impeccable palate—and she did—but it was more than that. It was more a matter of ethics. She had a quirky, stubborn sense of right and wrong in all matters pertaining to food. You could always tell how much she liked something just by looking at her face.

A few of the things that turned up her nose: potatoes cut in large or sloppy chunks, mostly in soup but also in potato salad; too-thick soups, which were dubbed “wallpaper paste;” the dubious spice, mace; floury or pale gravy; under-seasoned anything; the liberal use of cinnamon; overly sweet desserts; fussy food; funky liqueurs; muddled flavors.

Some things she loved: pan-frizzled pork chops with a salty crust; Manhattan clam chowder; a bowl of posole at La Fonda; platters of tomatoes and scallions sliced open and simply salted; kolaches with California apricots; slightly tart fruit pie with a flaky crust; sauerkraut; mayonnaise; chocolate.

But she didn’t fetishize food or put cooking on a pedestal. She cut onions in the palm of her hand, and apples for her pies with her thumb as a backstop. Cooking was an everyday affair meant for everyone—unpretentious and real. “If you like to eat, and you can read, you can cook,” she used to say.

Of the staple dishes she made hundreds or perhaps thousands of times in her life, she expected near-monastic purity and straightforwardness. She didn’t like any “guff.” But as Marcella Hazan says, “Simple is not the same as easy.” Which is why she never stopped critiquing her cooking—usually aloud and while you were eating it. It was, occasionally, exhausting. Sometimes, you just wanted to enjoy the pie, not hear about how it needed more lemon juice or a few minutes longer in the oven.

My grandma died before I opened my first restaurant, Vinaigrette, in Santa Fe, but I like to think I’ve inherited her palate and good food sense (all of the ladies in my family have), and that they’ve kept me out of trouble. But in the years since I opened my first restaurant, the food world has gotten harder to navigate. There is a relentless hunger for whatever is new and exotic, even if it’s ridiculous. The other day, I caught myself considering offering a Wheatgrass Latte for the cafe at Modern General, until Grandma’s face flashed before my eyes, with an expression that would have curdled nut milk.

And while working on the menu for the wine bar and bistro we were opening on Central Avenue in Albuquerque, I felt my clarity faltering. Everything I came up with was, in my grandma’s words, a bunch of malarkey. It had no soul. Trying to root out the one undone thing in the ever-expanding cosmos of food feels a fool’s errand, like riding a treadmill of trying-to-be-cool. I needed to get back to solid ground.

I about-faced to the dishes my mom and grandma made when I was growing up: Chicken Chasseur, Spare Ribs with Sauerkraut, Deviled Stew. I craved the way that food made me feel: cared for, safe, part of something.

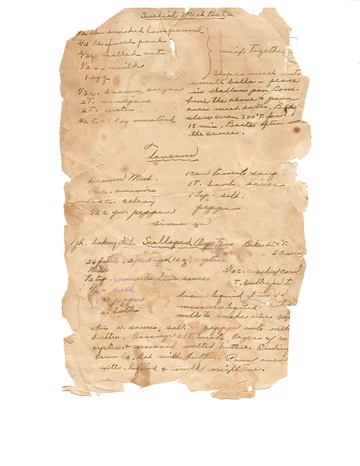

We named the bistro The Feel Good. Copies of old, battle-tested recipes, splotched with oil and sauce, yellowed with years, and crammed full of my grandma’s slanted, baroque cursive, hang in the hallways and behind the bar. This tidbit about Stuffed Green Peppers came from a letter to my aunt:

I take the tops from pepper and take out seeds. You can either leave it whole or cut in half. I usually buy large peppers and cut in half. I used to always put in a large pan and parboil, but have almost quit—the only advantage is it makes the peppers not quite so strong tasting. For my meat mixture I just dump. I usually make a big batch so I usually use about 1 ½ lbs of meat, cracker crumbs (about 15-20 single) (depends on how much you want to stretch the meat)…

It goes on—confusing and ambiguous the whole way through, regaling my poor Aunt Judy with every detail of her endless tinkering. For my grandma, a recipe was a living thing, always evolving, but also tethered to its beginnings.

Maybe looking backward is just nostalgia—that rosy perspective on the past that buffs away its harsh edges. Or maybe it’s a kind of acknowledgment that we are here on the shoulders of a whole lot of folks, many of them women, who have quietly held us all together, making now possible.

It feels good to honor that.

Erin Wade is the owner of Vinaigrette and Modern General in Santa Fe; Vinaigrette, Modern General and Feel Good in Albuquerque and Vinaigrette in Austin, Texas. As her website states, “Much of the produce for Santa Fe and Albuquerque is grown on Erin’s 10-acre farm in Nambe, New Mexico. A farm in Bastrop, Texas supports the Austin restaurant. Sustainability is a top priority. Food waste from the restaurants returns to the farm to feed the animals, and also gets composted back to the land to feed the healthy soil.”